-

About

Our Story

back- Our Mission

- Our Leadershio

- Accessibility

- Careers

- Diversity, Equity, Inclusion

- Learning Science

- Sustainability

Our Solutions

back

-

Community

Community

back- Newsroom

- Webinars on Demand

- Digital Community

- The Institute at Macmillan Learning

- English Community

- Psychology Community

- History Community

- Communication Community

- College Success Community

- Economics Community

- Institutional Solutions Community

- Nutrition Community

- Lab Solutions Community

- STEM Community

- Newsroom

Course Goals and Actions: Writing Project 1

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

Cincinnati is on my mind as I write this post. In the spring of 2007, I tutored elementary school students in Cincinnati’s Mount Auburn neighborhood, the same neighborhood where, after a traffic stop, Sam Dubose was shot in the head at point blank range and killed by a University of Cincinnati police officer on Sunday July 19, 2015.

The first day of tutoring, I was greeted in Mount Auburn by a laminated sign that announced this neighborhood school as a “failing school,” using the terminology from the No Child Left Behind Act. The sign was displayed prominently at the entrance to the school. The school was nearly 100% Black, and I was the nice white lady who had come to tutor the children for Ohio’s state exams in reading and writing.

Later that spring, I entered the school only to discover that the students were working on benchmark practice exams. I was taken to the cafeteria to help supervise children who had arrived late to school and, according to the rules, were not allowed to take the practice exams. A casual observer of that cafeteria scene might have described the students as rowdy and resistant. Yet that picture remains incomplete. The children were not sitting in their usual classrooms and they were not following their usual schedules. When I spoke with the children one-on-one, they shared their anger, their fears, and their passions. In other words, the children and I shared with each other our common humanity.

On that spring day in Mount Auburn, I learned what happens when we begin with stereotypes and work through the resulting cognitive dissonance. I also learned the importance of approaching our practice by “[developing] flexible strategies,” and moving forward with an open heart. In preparing for the new term later this month, the children of Mount Auburn remind me of the positive potentials of transformation—not only for our students, but also for our classrooms and ourselves.

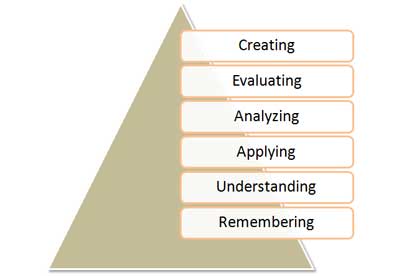

Below, you’ll find three lists to help prepare for the fall semester’s first new writing project. As detailed in my last post, the first project focuses on “forming and transforming stereotypes” and is based on a TED Talk by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. The first list is a set of criteria that presents several course goals that students will undertake for the Writing Project 1. The course goals are taken from the Framework for Success in Post-Secondary Writing. The second list focuses on course actions toward completing the assignment, using Bloom’s Taxonomy. The third list offers foundational assumptions behind course goals and actions.

Lists

1. Course Goals

- Be aware that it usually takes multiple drafts to create and complete a successful text

- Develop flexible strategies for generating, revising, editing, and proof-reading

- Understand writing as an open process that permits writers to use later invention and re-thinking to revise their work

2. Course Actions

- Applying basic disciplinary knowledge in a similar but unfamiliar context

- Evaluating a theory for the validity of its implications for college students and their instructors

- Creating a new interpretation

3. Foundational Assumptions

- The course is not remedial, and all students can learn to build on strengths. If writing leads to thought and action, then all students have basic disciplinary knowledge that can be applied to writing in the college classroom. All students in our courses have thought about matriculating to college and taken action to enroll in the course. The steps that led to those thoughts and actions hold the potential for success.

- To confront stereotypes and to deal with cognitive dissonance, students and instructors alike need to develop flexibility, re-think our work, and create new interpretations. We can practice these skills through steps in the writing process, and in completing the writing process to create a new essay that has never before existed.

- This practice is not necessarily easy, and the results may not become visible until long after the process has ended. As we practice editing and proofreading in a classroom community, we learn to read more closely and to pay more careful attention to the world around us. Every person who attempts this process will carry different strengths and discover different struggles. The struggles can become short-term goals for continued practice. This process is equally true for students and instructors.