-

About

Our Story

back- Our Mission

- Our Leadershio

- Accessibility

- Careers

- Diversity, Equity, Inclusion

- Learning Science

- Sustainability

Our Solutions

back

-

Community

Community

back- Newsroom

- Webinars on Demand

- Digital Community

- The Institute at Macmillan Learning

- English Community

- Psychology Community

- History Community

- Communication Community

- College Success Community

- Economics Community

- Institutional Solutions Community

- Nutrition Community

- Lab Solutions Community

- STEM Community

- Newsroom

- Macmillan Community

- :

- Communication Community

- :

- Communication Blog

Communication Blog

Options

- Mark all as New

- Mark all as Read

- Float this item to the top

- Subscribe

- Bookmark

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

Communication Blog

Macmillan Employee

09-27-2023

08:39 AM

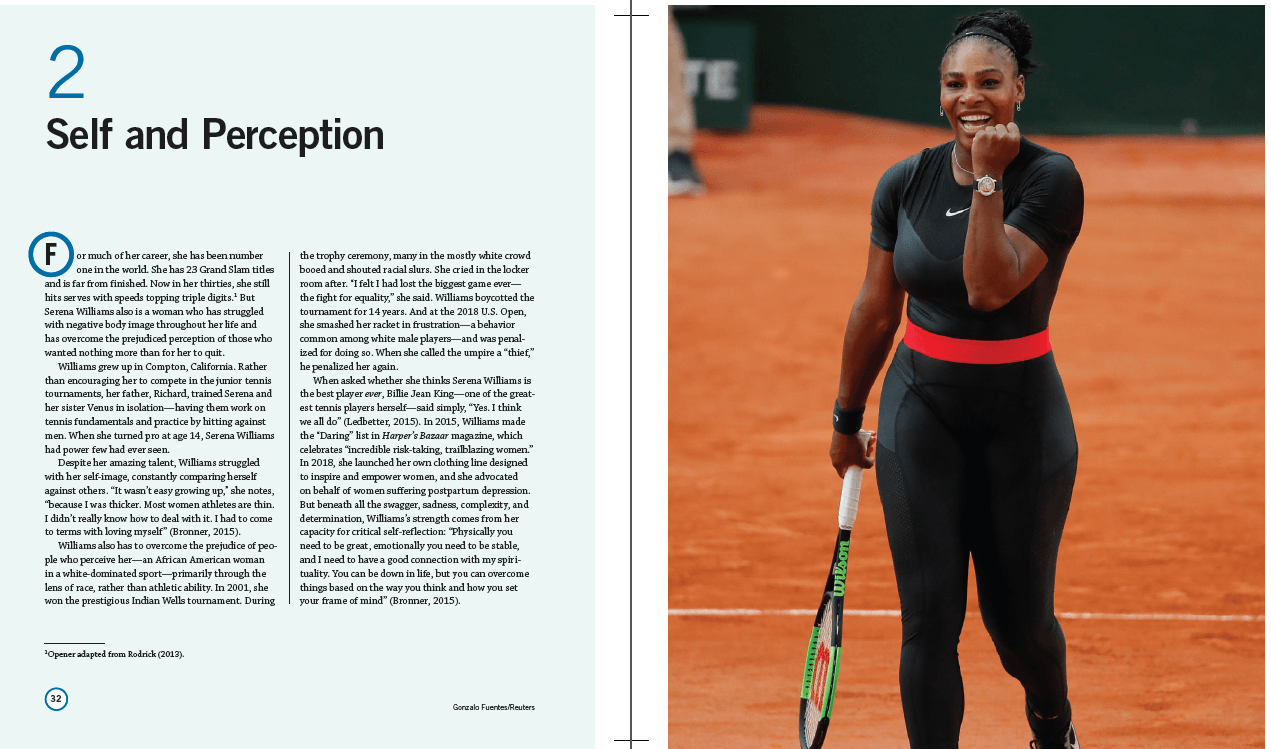

Discover thought-provoking Communication topics in the 13th edition of "Media & Culture" with co-authors Bettina Fabos & Christopher Martin. These captivating new modules, featured in Achieve this December, shed light on a variety of topical issues -- in this video the authors explore one of those very topics: social media's impact on mental health.

Exploring the evolution from its early days in 2004 to the present digital era, issues like body dysmorphia and depression have spiked as a result of the online comparison-based ecosystem. This video offers insightful analyses of mental health challenges and offers some attainable small steps towards mitigating those issues.

... View more

0

1

2,497

Macmillan Employee

10-21-2021

09:42 AM

Loneliness, unhappiness & the connection to interpersonal communication skills

Loneliness is on the rise and has been since the early 2000s. With ongoing concerns about students’ mental health during the pandemic, it’s more important than ever to address the root of the problem: the lack of interpersonal communication.

Why are students more lonely and unhappy than ever? Research from psychologist and Macmillan Learning author David Myers found that while some factors like religion, volunteering and fitness have a slight impact on happiness, the thing that makes the most impact is having satisfying relationships. Not just romantic relationships, but also connections with friends, family, co-workers, and fellow students. The way to develop these meaningful, and sustaining relationships is interpersonal communication.

Addressing the Lack of Interpersonal Communication in the Classroom

It’s challenging to address lack of interpersonal communication when students are more dependent than ever on technology in many aspects of their lives -- from their regular access to social media to their remote classes while they were confined during the pandemic. The screen that has allowed them to connect with people is simultaneously isolating them as well as becoming a scale for self esteem (which is a concept worthy of an entire blog.)

But there are steps instructors can take to help students to establish and enhance interpersonal communications in and beyond the classroom. According to Steven McCornack, Professor at University of Alabama at Birmingham, “Sustaining relationships is a mental health imperative and interpersonal comms is a way to address it.”

8 Tips for Teaching & Developing Interpersonal Skills in Students

Last week’s webinar about interpersonal relationships in a post-COVID world with professors and authors Steven McCormack and Kelly Morrison, Professor of Communication Studies at the University of Alabama at Birmingham hosted by Macmillan Learning introduced some steps that instructors can take both in and out of the classroom to help develop these skills in students. While some tips are specific to Communication classes, others can be used in just about any class. Here are eight tips:

1. Don’t start the semester with a “syllabus day.”

Steven and Kelly start out class with a question: “What is the most important thing that drives your life’s happiness.” This helps develop community within the class and gets the students to start talking. And, for their class in particular, it’s helpful to lead into the content as to why their course on interpersonal communication is important.

2. Use name tags in class for in-person classes.

While many students can identify the faces of the other students in their class, not as many are familiar with their names. Having name tags is like opening a door to say hello, and continues throughout the semester to create community.

3. Have music on before class.

Having music creates an environment that encourages conversations. Steven consults his son on a playlist so that he has the most current music on, whereas Kelly prefers more upbeat music. No matter the kind, music is a great conversation starter.

4. Gently push students not to use devices.

While the screen enables students to connect with each other in the digital space, it is also very isolating -- and not just because students are looking down at their devices instead of engaging with their surroundings hindering conversations. Research correlates social media consumption and social isolation; it’s possible to plot someone's feelings of isolation by monitoring the amount of time per day they spend on social media, in large part because they’re doing social comparisons and feeling worse about themselves.

5. Use the “introduce yourself to a stranger” assignment.

This assignment asks students to introduce themselves to a specified number of people they hadn’t met before either every day or every week. The assignment aspect of it gives students a valid excuse for approaching someone they didn’t know and starting a conversation, helping to remove some of the shyness and intimidation some students may feel. This has led to many students finding common interests or even making new friends, helping them to feel less lonely.

6. Advise students about Self-Discrepancy Theory.

The theory purports that self-esteem, in large part, derives from how we compare ourselves to two standards -- who we believe we should be and what we believe the ideal is. Students’ own self-concept will benefit when they are mindful of their inputs and understand that social media should not function as a scale for self-esteem because many things being posted are fictional and non-attainable. Empower students to know that they alone have the power to change the comparisons, as they reside in their own thoughts.

7. Help get conversations started.

Students can engage with each other in discussion boards or in breakout rooms, giving them the ability to connect with and learn from each other. Instructors can use ice-breaker questions like “what would the title of your life’s story be, and why” to allow students to better get to know each other.

8. Use video.

In addition to being more efficient than sending emails back and forth for hours on end, video conferencing with students helps to build connections with instructors and each other. Instructors can meet with students individually or in small groups. In asynchronous classes, video introductions can be used to allow students to get to know each other and discover common interests.

How Do You Promote Interpersonal Skills in Your Classroom?

As an Interpersonal Communications instructor, Kelly opens her classes by underscoring the importance of having sustaining relationships, and the steps outlined above are some ways to nurture their development, but that’s just one of many options. These eight ideas are some of many designed to help support the development of interpersonal communications -- leading to happier and more successful students. The close relationships that students develop, more than money or fame, are what keep people them throughout their lives. “The way that students can get there is through interpersonal communication,” she noted.

What tips or activities do you promote in your classroom for helping students develop interpersonal communication skills? Tell us in the comments below! To watch the full webinar and access the slide deck, click here. Learn more & request a copy of Steve and Kelly’s new edition of Reflect and Relate: An Introduction to Interpersonal.

... View more

0

0

2,900

Macmillan Employee

01-15-2021

10:00 AM

Blog and activity developed and written by Laura Sells, Communication Instructor, Nicolet College. Sells is the author of the Instructor's Manual for Joshua Gunn's Speech Craft. At the start of every semester, I remind myself about the old saw “start as you intend to proceed.” Crucial to setting the tone for the semester, the first day of class is a rich opportunity that many instructors unknowingly misspend and then wonder why the semester proceeds with students who are disengaged or reticent to participate in discussion. If instructors kick off their class without meaningful engagement, students tend to limit their participation and investment. In online and Zoom settings, something we’re all a little more familiar with now, engagement can be difficult to cultivate, making the process of tone-setting even more crucial. Going over the legalese of the syllabus can set a pattern that we will lecture and spoon-feed students the instructions for the duration of the course. Yet we often feel pressured to cover syllabus material in great detail. Online instructors have the right approach when they quiz students over the syllabus and policies during the first week of class, because it shows students how to take responsibility for their own learning and requires students to engage with the material. But some may think this approach impractical and heavy handed for face-to-face and Zoom-style classes. What follows is an active-learning activity for the first day of class to get students talking in groups about the syllabus, processing policy statements, and thinking about what will happen in the course. It also serves as a productive ice breaker to get students conversing with one another. It circumvents legalistic droning, though it does not eliminate it entirely. It also reduces the number of first-day repeat questions, because students often answer their own questions for each other through their small group discussions. ACTIVITY Setup: Have students review the syllabus and make notes or write questions in the margins. Tell students that you will be doing an activity with the syllabus instead of going over it with them the way it’s traditionally done in most classes, so they need to read the syllabus instead of waiting for you to cover it. If they try to ask questions, gently defer them for the group activity. Step 1: Write on the board, show a document/PowerPoint, or give a handout with the three questions below. Have students write the answers to the questions. Pace them. Depending on how much time you allot for this activity, it should take about 5 – 7 minutes to answer these questions. 1. What are your hopes about this class? 2. What are your fears about this class? 3. What are your questions about this class, the syllabus, the textbook, the assignments, giving speeches, the instructor, etc.? Step 2: Put students in small groups or breakout rooms of about 4 or 5. Remember, the larger the size of the group, the longer it will take to finish the activity. Tell students to introduce themselves, discuss what they wrote,, and pick someone to report back to the class. Tell them to also pick their #1 burning question that they had for question 3. So, for example, they are usually able to figure out the answers to most of their questions through discussion, but they’ll have one or two questions left over that become their questions to ask during the class discussion. Once students are in groups, be sure to check in at least twice to set the pattern of good group work. The first time, check for understanding, but deflect questions about class for the debriefing. The second time, check pacing and make sure the group picked someone to report back to class. This helps keeps students on task. Step 2 can be accomplished fairly quickly, in about five minutes, but if you allow longer time, the students have an opportunity to bond over commonalities and the activity becomes an icebreaker. Pay attention to the flow of conversation and regroup when the flow of conversation has shifted to general social talk or awkward silence. Step 3: Go from group to group and call on the student who volunteered to report back to class. Have that student: 1. Introduce the group’s members 2. Summarize the answers to questions #1 and #2 3. Ask the group’s burning question Step 4: After answering the group’s burning question, the instructor can ask for a second question from the group or go on to the next group as desired. Once all the questions are asked and answered, usually all the primary points that need coverage are addressed and the instructor can cover the finer points more quickly. Although covering the syllabus in this fashion is less linear, it is more interactive, and the students have a hands-on experience with the class documents and with peer interaction. This promotes a tone in class that is less dependent on the instructor for direction. It also stands in for an icebreaker that opens the air for discussion in the next class. Bonus Step 5: The instructor can collect the answers and review hopes and fears aloud anonymously and talk about the commonalities, pointing out the common threads of communication apprehension, desire for a good grade, keeping up with the work, and so on, and talk about how these will be handled in the class. This can help establish community in the class. Managing the first day of class is crucial to a successful semester. Students are wondering what they have gotten themselves into and instructors are wondering how many times they will have to say “It’s in the syllabus.” This activity acts as a fun middle ground that sets a positive tone for all. What are your strategies for covering the syllabus on the first day? Comment and let us know!

... View more

1

0

3,990

joseph_ortiz

Migrated Account

11-07-2019

09:05 AM

In the introductory human communication course or public speaking course, it can be challenging for students to see speech preparation as a developmental process. Many students come into introductory courses having done oral presentations for other academic classes. For example, they may have had a presentation assignment in an art history or business class. As a result, these students are accustomed to planning their speeches and presentations by using a PowerPoint template or simply writing down a “grocery list” of topics to cover.

How to Prepare a Speech in 5 Steps

To encourage students to be more intentional in their speech preparation, I teach a five-step model: Think, Investigate, Compose, Rehearse, and Revise. Think about your topic and audience; investigate or research the topic; compose an outline; rehearse your speech, and revise the outline according to feedback received from your rehearsal. This five-step model for planning a speech is the basis for both lessons and learning activities.

Teaching Students this Speech Preparation Process

Students are expected to apply this five-step model in preparing their speech assignment and to make their preparation visible through a portfolio assignment. Specifically, written documentation of how the student has applied each of the five steps is organized into a folder and submitted for grading. Figure 1 below outlines the five-step model along with the type of evidence to be included in the portfolio.

The portfolio assignment encourages students to be more intentional in developing their speeches and helps them see speech-making as a developmental process. Additionally, it provides instructors with a complete “snapshot” of the preparation that went into the speech, which then supports meaningful and constructive feedback to students.

Five Steps in Making Your Speech Preparation Visible (Rubric Model)

What

Evidence

Think

Brainstorm inspiration for the topic

Analyze the situation and the audience

Narrow the topic

Develop a working thesis statement

Brainstormed list or written rationale for topic choice.

Complete audience analysis survey.

Written notes that show the process of narrowing a topic and the development of a working thesis statement.

Investigate

Locate resources: articles, books and websites

Keep research cards or notes with bibliographic citations

Frame your thesis statement

Sampling of search terms, bibliographic citations, and notes to show research efforts.

Final thesis statement.

Compose

Identify main points and supporting material

Develop a working draft of the outline of the speech body

Prepare introduction and conclusion

Develop a polished draft of the speech outline

Prepare presentation aids

Preparation outline drafts.

Notes or outline drafts of speech introduction and conclusion.

Notes on possible presentation aids.

Rehearse

Prepare necessary speech notes

Give the speech aloud

Practice with presentation aids

Work on vocal and nonverbal delivery

Obtain feedback from another person

Drafts of speaker notes or delivery outline.

Date/time record of rehearsal efforts.

Written summary or notes from another

person on rehearsal feedback.

Revise

Develop a final speech outline as indicated by practice feedback

Final speech outline.

What advice or lesson plans do you use for helping your students prepare for oral presentations? Let us know in the comments below!

For more information on this and other communication topics, please see Choices and Connections, Third Edition, by Joseph Ortiz and Steven McCornack, newly available at macmillanlearning.com.

... View more

2

0

35.5K

Author

03-21-2019

08:00 AM

As insults go, “fake news” has not yet reached the point of vacuity of, say, “your mother wears army boots.” Because of its excessive and less-than-strategic usage, it is edging into cliché territory. That is a knife that, though dulling, cuts both ways. That it’s being used to the point of triteness means that many are comfortable slinging that particular bit of slander about. This former journalist repudiates the ease with which the phrase is used to denounce or discredit critical or unflattering reportage. That the term is inelegant is a bit beside the point, I think, because those who are inclined to reach for it are not hunting for le mot juste. They are most likely scooping up verbalisms that they imagine are more cutting than cunning. Peers in classrooms and newsrooms have asked me on many occasions to weigh in on what “fake news” means and how to respond to or guard against it. My response has most often been that responsible reporting is its own defense. Bluster won’t quiet a bully whose purpose is to cow and not correct so I hardly ever broach the matter of silencing a crank. Dotting I’s and Crossing T’s, eschewing cut corners and holding firm on never publishing supposition or rumor is the truest armor of a news reporter. I have, however, given more thought on ways to help news consumers better identify reportage that falls short of traditional journalistic standards either because of incompetence or fraudulence. I call them the Three C’s of Fake News: Content. News consumers should first examine the content of the article or report. Consider these questions: What information is being shared and is the information attributed to a source that is named. If the source is unnamed, is it clear why the source is not being named – that is, is it clear to you what is at stake by revealing this information – termination of employment, bodily harm? Does the threat seem reasonable based on the nature of the information? If the information is challenging previous reports or popular thinking about some issue, is there evidence being offered as support or is the challenge more a matter of perception or viewpoint? Ask yourself why you should abandon what you have believed was true about the matter for something that is not demonstrably or verifiably true. Additionally, you should ask if other sources have reported similar findings or if the information being shared is an “exclusive.” Exclusives can indeed result from the industry and resourcefulness of a news organization, or it can be information that was dressed and planted – or leaked -- with the hopes it of passing inspection, especially when deadlines are looming or it’s a slow news day. Much mischief finds its way into the news hole that way. Construction. News consumers should also consider the news’ construction because clues to fraudulence might be found in its crafting. Consumers might consider if the article or report focuses on the authenticity or truthfulness of its information by citing sources by name, attributing all facts and opinions and letting what is disclosed speak for itself. However, if the article is crafted around innuendos and suppositions and masks facts in inferences and hedges conclusions, red flags should go up. These constructions are often marked by language like “believe,” “think,” or “feel” to refer to sources other than the writer. The article might contain large sections of unattributed information, leaving readers to wonder whose perspective or viewpoint is being represented. This could be a sign of fictionalization. News consumers can gauge the authenticity of a report by the number of times the writer uses the construction “source + said,” as in “Mayor Brown said on Monday ….” Reports that are thoroughly attributed and transparent are much less likely to be hawking fakery. Verification and corroboration are the pillars of responsible journalism. Articles that include personal experiences for which there were no other witnesses and thus cannot be verified are not necessarily fake; they should be weighed differently and the information assessed with the understanding it is the speaker’s account. Articles that refer to other reports should include citations or working links to the source material. Examining the linked material for political or promotional affiliations would be wise. Common Sense. And, finally, readers and viewers should consume news with healthy portions of common sense. Most simply put, news consumers should ask if the report makes sense based on common knowledge, previous reporting or even their personal experiences. Do some events seem too good, too appropriate or too convenient to be true?Just because an article does not make sense or smells funny does not necessarily mean the item is fake; it does mean one should handle the information with caution and scrub it using the guidelines above. If, in the end, the article writer’s position seems to be more combative or confrontational than informative, then the news consumer is likely not dining on news or at the very least competent reporting. It might be propaganda. And, as we all know, propaganda was “fake news” before fake news was cool.

... View more

0

0

3,801

Macmillan Employee

03-12-2019

12:57 PM

Macmillan’s first edition public speaking text, Speech Craft, has a personality of its own. Fittingly, its corresponding LaunchPad reflects that personality, as the book’s author, Joshua Gunn helped develop several of the activities for it! As your Learning Solutions Specialist for Communication, let me walk you through these features as unique as the author himself. One of the most exciting New LaunchPad feature are Digital Dives, written by Joshua Gunn himself. Students often struggle to apply what they read to their actual presentations. These were designed to help with that. Each chapter (except for chapter 12) engages students in topics at a deeper level through the use of podcasts, videos, and critical thinking questions, ranging from speeches given in the real world to real student speeches. They also promote Community Building by engaging students to think about the audience as a community. An example of a speech from the real world can be found in Chapter 9, on Style and Language. It focuses on the use Repetition and Rhythm, and asks students to first read the transcript of a eulogy given by Barack Obama and then watch a video of it. What students take away from this is that while writing repetition into a speech seems silly or pointless, seeing and hearing that repetition (and the rhythm of it – the way in which its repeated) helps students to realize it’s importance and impact. Chapter 11 on Presentation Aids looks at understanding the slide in a classroom speech. Students get to looks at its role in a speech - which is meant to enhance your presentation, not give it for you or distract from it. See sample screenshots below: Clearly, one of these is great, the other…not so much. So, students are asked the Questions: Which speaker presented their slide show more effectively? How could each speaker improve his or her delivery? The author has also left his mark on our new sample speeches. The Car Cookery full length Informative Speech is actually a speech he presented, and in LaunchPad it is delivered by a student. And, we can’t forget about the instructors. Joshua helped design the chapter slides, and the instructor resource manual was written by Joshua’s mentor, Laura Sells. Of course, the LaunchPad also contains all the other great LP content you’ve come to expect from Macmillan, including an ebook, outlining tools, LearningCurve Adaptive quizzing, and our new Video Assessment Program – Powered by GoReact. If you’d like to learn more or get assistance setting up your LaunchPad course space, sign up for a demo with your LSS Specialist: http://www.macmillanhighered.com/Catalog/support.aspx

... View more

1

0

2,631

newspapernerd

Migrated Account

08-16-2018

01:14 PM

In my journalism classes, I used to teach using the building-block method. I would set up my class in chunks: present the material, assign a story, require follow up reports and peer reviews, and have students turn in an assignment. This process took about four weeks. Then I would do it again with new material, a new kind of story, and more follow-ups that resulted in another story. At this rate, I was lucky if my students could write four stories a semester. The building-block method is good for perfecting old material before moving on to new material, but it went against my teaching philosophy for writing: "practice makes perfect." Learning by Doing Short deadlines and multiple priorities are hallmarks of the newsroom. No one has time to help anyone else because they’re so busy themselves. You don’t get a long, leisurely introduction to the job. You just do it. Journalism, like public speaking, takes practice, practice, and more practice. You can’t teach someone how to feel when they’re interviewing an intimidating figure. You can’t teach them how to know when someone’s lying to them. You can’t teach them to know when the story just isn’t going to work out. So how can you give your students lots of practical experience in doing what the pros do? Turn your classroom into a newsroom. To replicate the newsroom, turn the first three weeks of the semester into Journalism Boot Camp, covering newsworthiness, the inverted pyramid, research, interviewing, and anything else you feel it's necessary to cover in a class setting. After that, assign stories with deadlines and send the students out for reporting. The time they spend reporting takes the place of class time. By the end of the semester, students will write around 10 news stories. But, what about all that grading? Imagine 20 students per class, 10 assignments per semester. That’s 200 assignments to grade per class. What if you teach four classes? Now you’re up to 800 assignments. And that doesn’t include the labs, quizzes and tests that require attention. That’s why the class is like a newsroom. In my class, students get four assignments at a time and can turn them in in any order they like. There’s a catch: when they turn in an assignment, they must make an appointment with me the next week to edit it. Since they are out working on stories, my class time is freed up for individual appointments. Each student gets 10 to 15 minutes of my undivided attention as I edit (grade) their assignment. Most of my grading is done on the spot, in the classroom, with the student. No more sending back assignments with feedback they never read. No more wondering if they understand my feedback, or even care. Now I get to look them in the eye. Collaboration I do bring them back into class for a week near midterms and again near the end of the semester. They discuss how their stories have gone. They talk about what went well and what didn’t, much like reporters do in the newsroom. Students share how they handled situations that others found troublesome. They take suggestions from each other and offer their advice. Students have even set up outside groups to discuss assignments and how to approach them. Our “newsroom” has become more collaborative. The best part is that by the end of the semester they’ve gained a great deal of confidence, and I really enjoy grading their work. Marti Gayle Harvey is a Lecturer at the University of Texas at Arlington, where she teaches journalism.

... View more

1

0

3,134

newspapernerd

Migrated Account

08-16-2018

01:04 PM

USING GROUPS TO TEACH WRITING Some see writing as a solitary process. Some teach it as a solitary process. However, teaching writing as a group activity lets students explore how others approach learning the craft, allowing them to come up with their own approach. The writing process generally goes from thinking of a topic, collecting information, crafting a message and revising it. When done in a solitary environment, feedback is important but lagging because of grading time. When done in groups, feedback is immediate and, since it comes from peers, it seems more like a conversation than a lecture. HOW IT STARTED I use a form of flip teaching. It consists of students being introduced to a concept through online content by reviewing materials for a basic understanding. When students come to class they work on a low-points, graded lab, applying the concepts to a concrete example. Finally, a classroom discussion among the groups allows for a review of the lab allowing the teacher to guide the discussion making sure concepts are covered and understood. I found that the lab portion needed more pizzazz. Some students would finish labs early and just sit there waiting on everyone else. Others pulled out their phones. The room was quiet, and students were bored. I was, too. One day I put them in groups of three, mainly because I could cut down my grading, but it also kept the room from sounding like a crypt. They had to talk to each other. HOW DID IT GO? I had them work on changing a story from passive to active voice. This is one of the hardest concepts for young writers. They must determine if the subject is doing something or if something is being done to it. The exercise was a hit. I caught them explaining concepts to each other. They got immediate feedback. The lab results were much better, too. They “got it” much faster. And they laughed. They laughed at each other. They laughed at themselves. Mostly they laughed when they tried something and it didn’t work. Eavesdropping on their conversations convinced me that they were having fun. They were learning. SO WHAT? I came to the conclusion that they learn better from each other than they do from me. One reason is that group work allows for highly differentiated learning styles. Visual, auditory, reading/writing and kinesthetic learning styles adapt spontaneously to group work. If someone needs to hear it, there is always someone in the group willing to let them read it to them. If someone needs to do it, they can “break it down” for the other group members. Visual learners will understand the structure and reading/writing learners are usually the scribes of the group. Another reason that group work works is because it is fun. Especially if it’s nothing more than a low-points lab. They get to explore concepts, don’t have a lot to lose if they’re wrong, and they get to do more than sit around on their phones waiting for the rest of the class to finish.

... View more

1

0

3,255

twinjenn98

Migrated Account

08-02-2018

07:57 PM

We’ve all worked on a team at some point, but have you ever been told you would be on a team and cringed at the thought because of a previous bad experience? As we have more opportunities to work with teams, we realize that there are people who we would LOVE to work with again at some point, and there are others who we would prefer to leave in the past. Whatever your experience, it is safe to say that every project that involves group work teaches us a lesson about relationships. As a teacher, I sometimes use class time to observe and discuss group dynamics. A student once said to me, “team work makes the dream work,” and yes, it does! At least, it does if there is cohesion, trust, engagement, and reliability. What happens when the team doesn’t work? Will you remember who worked their tails off? Will you remember those who still have their tails because of the lack of effort? Sure, you will; the memory of the efforts or lack thereof will always be there. Present behaviors can have a future impact, whether we realize it or not. Pareto’s Law, also known as the 80/20 rule, is a theory that explains that 80 percent of the output from a given situation or system is determined by 20 percent of the input. Speaking in terms of employee performance, this theory suggests that 20% of the people do 80% of the work. Have you ever experienced that? If not, you might at some point. My point is this: work ethic matters because people are watching, and no job comes with the security of lifetime employment. Whether you realize it or not, you are subconsciously observing people and they are observing you. You know just from your own observations whether or not you would want to work with a particular person again. You remember those who are great, those who are less than great, and forget those who fly under the radar and get lost in the middle. Let’s be honest – you’re not going to recommend someone forgettable for a job anytime soon. Establishing solid relationships and putting your best foot forward are important because when things go awry in an organization and labor cuts need to be made, you need others who can vouch for your work ethic. You need people who will say, “Send me your resume so that I can forward it to…” As an educator, I put my best foot forward because I know my students are watching me just as I am watching them. I know which ones are dependable and reliable; I also know the ones who are not. I enjoy writing recommendations for those who try, and I write recommendations for those I would hire. I do not feel comfortable recommending someone for a position I would not hire. And who knows? My students might be in a position to hire me one day, so I better be the best possible leader for them. The key takeaway here is that present behavior impacts future opportunities. Through the power of observation, opportunities can be created or lost. Strive to be in the 20% of the workforce that gets remembered for your impact, and your future self will thank you. Professionally yours,

... View more

0

2

3,585

twinjenn98

Migrated Account

06-21-2018

10:08 AM

Let’s talk persuasion. In my days as a campus recruiter, I was often called upon to meet with prospective student athletes (and their families) to give them helpful information about the university admissions process. At some point along the way, one of the coaches informed me that 100% of the athletes with whom I met signed with the university. I was delighted, yet somewhat shocked, to hear that information since I truly was not trying to be persuasive in my conversational approach – I was simply being informative yet sincere. I bring this up because our words (and behaviors) inspire action (or inaction), whether we realize it or not. Fast forward a few years into the classroom, and I am influencing students to essentially buy into course concepts every day. I find that whatever seeds I plant into the minds of my listeners typically get regurgitated. For example, if I tell my students that a project is relatively easy, they buy into that idea and provide me feedback that it was, in fact, easy. If I tell students that same project will be difficult or challenging, they face it with fear and a sense of being overwhelmed. What happens when people get overwhelmed? They shut down. Language matters. How we frame ideas matters. As educators, we need to set a persuasive tone and use influential language that is filled with possibilities and opportunities so that our students flourish. We regularly draw upon Aristotle’s persuasive appeals when teaching imperative lessons, but is there anything in particular we can do to help our ideas stick? Let’s change the narrative to being “positively influential” Sometimes, people attach a negative connotation to the word persuasion. When I think back to my days in recruitment and my present-day classroom discussions, I never felt like I was “persuading” anyone. When I overthink my persuasive tactics, I worry I might come across as “rehearsed” or “sales-y”; I prefer to use the phrase “positively influential”. The best way to plant positive seeds is to do it in such a way that people do not even realize they are being influenced. It is important to note that being influential is both language-based and behavior-based. In your approach to be influential, consider employing some of these ideas to drive home ethos, logos, and pathos even further: Use confirming language. Young, moldable minds believe what we tell them to believe. Confirming language such as, “I really liked your contribution to today’s discussion,” lets students know that you are listening to them and that you truly value their input. This has a great impact on their own identify and can affect their academics, how they communicate with others, and ultimately, how they influence others. Paula Denton, EdD and author of The Power of Our Words: Teacher Language that Helps Children Learn and Founder of the Responsive Classroom, notes, “teacher language influences students…It shapes how students think and act and, ultimately, how they learn.” While Dr. Denton’s focus is on interactions within an elementary setting, it is safe to assume that language matters well beyond grade school years. Dr. Denton suggests that by being direct, by conveying our faith in students’ abilities, by focusing on actions, by keeping things brief, and by knowing when to be silent, we are fostering a respectful and positive community. Speak to your listener’s needs. People buy into ideas when it benefits them. Make the information matter to those who are in your presence. It is up to your audience to determine if your message is communicated effectively. Nancy Duarte speaks about the power to change the world in her TedxEast Talk; more specifically, she notes, “It's easy to feel, as the presenter, that you're the star of the show. I realized right away, that that's really broken. Because I have an idea, I can put it out there, but if you guys don't grab that idea and hold it as dear, the idea goes nowhere and the world is never changed. So in reality, the presenter isn't the hero, the audience is the hero of our idea.” Be an Equal. It is important to be able to command a classroom so that we do not lose sight of our desired objectives, but one of my mentors once advised, “you gain power when you lose the power trip.” I have found this approach to work great in a classroom. Be Honest. Even if people ask you hard questions, be honest in your approach to providing information and answering questions. People appreciate honesty and would rather not be persuaded through a false hope; false hope leads to disappointment and distrust. Be Responsive, Timely and Follow Through. Do what you say you’ll do. If your listener has a question with which you do not have a firm response, you may offer to get back to them. Always get back to them in a timely manner. You will build respect and trust. Be Genuine and Kind. Providing information in a genuine and sincere way comes across in various ways. From the tone of our voice to our gestures to our facial expressions to eye contact, these nonverbal behaviors are typically not rehearsed when we are speaking in the moment, authentically. Being authentic creates a sense of trust. Tell a Story. Offering a story helps seal a relatable appeal. One of my mentors once told me, “if you start getting some glazed eyes in the audience, tell a personal story to reel them back in.” People remember stories because they can visualize them, and it also reassures them that you are also a human. Whether we are inside or outside of the classroom, from what we say to how we say it, we are planting seeds in the minds of those who are giving us their attention. Words and behaviors are powerful tools and we should use them in such a way to help create successful contributors to society. If we do a great job as educators, we will see those seeds flourish into something phenomenal. Professionally yours, Jennifer Mullen

... View more

1

0

2,916

Macmillan Employee

07-11-2016

07:36 AM

Joseph Ortiz is a Professor at Scottsdale Community College in Scottsdale, AZ. He is the author of Choices & Connections: An Introduction to Communication, 2e. Q. What courses are you teaching next semester? JO: During the fall term, I teach two courses: Introduction to Human Communication and Interpersonal Communication. For the spring term, an introductory small group communication course—and occasionally digital storytelling-- is added to the mix. Q: What advice do you give your students who have public speaking anxiety or general communication apprehension? JO: Start your preparation early. Know the central idea to be communicated. Compose a structured outline and practice with it. Get feedback from trusted others. I design my course in a way that builds upon these steps using low-stakes speech assignments to help students gain confidence. Q: What has been your favorite course to teach and why? What advice do you have for other instructors who teach this course? JO: I really enjoy teaching the Introduction to Human Communication. It’s an opportunity to introduce students to the breadth and richness of our discipline while providing them with life skills. My advice to others teaching this course is to identify three to five “take-aways” for the course. In other words, several years from now, what do you want students to remember about your course? For example, I want students to be poised and confident when presenting messages. Develop ways of integrating these “big ideas” as recurring themes in your lesson planning, assignments, and assessments. Q: What are some of your research interests? JO: The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL). Q: If you could create (and teach) a brand new course for your department, what would it be? JO: Communication Ethics and Responsibility. Q: What do you think is one of the biggest challenges students face now when they enter college? JO: Many students at a community college are uncertain about their academic purpose. Additionally, they are often underprepared for college level work. I respond to this challenge by creating an engaging and personally relevant course experience, and by having early interventions to direct students to academic support resources when needed. I’m fortunate to be on a campus with highly qualified staff that provides high-impact tutorial support, counseling services, and academic advisement. Q: What motivates you to continue teaching? JO: Students amaze and challenge me. I love learning about their views of relationships, technology, social issues, and popular culture. I remain a student at heart without compromising the boundary of professionalism. On a personal note... Q: How do you spend your time when you're not teaching? JO: I treasure time with my family. I also enjoy reading and following sports. During the summer, I succumb to the Siren Song of Netflix; I’m presently binging on Cheers. Q: What are some of your hobbies? JO: I’m a leisure cyclist. Scottsdale has a system of beautiful bike paths for riding. I also enjoy discovering craft beers, and I’m trying to find the nerve to brew my own! Q: If you hadn't pursued a career in higher education, what career path do you think you would have chosen? JO: I started college with plans to attend law school. I would likely be practicing law in the public sector focusing on human rights, life quality, and social justice. Q: What was the last book you read? JO: Lab Girl by Hope Jahren. It is an insightful look at one woman’s experience in the STEM field with detours into fascinating facts about botany and ecology. Q: What book has influenced you most? JO: It’s tough to identify a single book. From a personal standpoint, I would have to say, To Have or To Be? By Erich Fromm. The book broadened my perspective of the fundamental question of what it means to live happily. Among the books that influenced my teaching is The New Peoplemaking by Virginia Satir. I read her work early in my career, and it helped shape my experiential approach to teaching communication skills. Q: Where is one place you want to travel to, but have never been? JO: I want to see the Vatican for its religious and historical significance, and the art. Q: When you sit down to listen to music, which artists or genres do you go to most? JO: My musical taste is eclectic, ranging from composer, John Rutter, to Pitbull. But my playlist is heavily populated with 70’s classic rock and pop music. And I will stop anything I’m doing and listen reverently to any music written or produced by Burt Bacharach. Q: What is something you want to learn in the next year (Communication-related or otherwise)? JO: Although I can cultivate a great flowerbed, I’m a frustrated vegetable gardener. I want to get better at container gardening, especially root vegetables. Q: What is one thing people would be surprised to learn about you (i.e. What's your "fun fact"?)? JO: I was a competitive long distance runner in college. In the late 70’s, I was a founding member of a still thriving running club (over 500 members now) in Southeast Texas called, The Sea Rim Striders (www.searimstriders.org/whoweare.php).

... View more

0

0

2,154

adam_leipzig

Migrated Account

06-28-2016

10:17 PM

Summer's here, and this peach caught my eye. Set on the blue ledge of my office, it became the perfect example of complementary colors. When we're preparing a movie, we think about complementary colors, and all kinds of color combinations. I ask my students to do the same for their video projects. Colors convey meaning, emotion, and genre. They are part of telling a visual story. For example, thrillers generally have deep, dark blacks and highly contrasting colors. Documentaries -- or movies that try to feel documentary-like -- use a color palette that is narrower. When I was producing Titus, the first film Julie Taymor directed, she didn't want the color green in the movie. Green conveys hope, and Julie didn't think Shakespeare's Titus Andronicus should feel hopeful. We can ask our students: Do you want the colors to pop? Do you want your video to feel more monochromatic? Simply paying attention to colors, and using color as part of your design, can make a video feel much more professional. Blue and orange are "complementary colors," and when you put them next to each other, as in this photo, they seem to vibrate. I found it striking to see such a powerful example of color-in-action right in front of me. You probably remember the color wheel. It has six colors arrayed around a white central circle. Red is opposite green; yellow is opposite purple; blue is opposite orange. The color wheel isn't random. Those opposing colors are called "complementary" due to the physical nature of the human eye. If you stare at a blue wall for a long time and then look at a white wall, you will see an orange after-image. Why? Because the color receptors in your eye become tired looking at the blue wall, so they relax when you look at the white wall, and your brain "sees" that as orange for a few moments. That's why complementary colors are so powerful when you put them right next to each other. But enough of the science. Colors are just one more way we can convey narrative and emotion. When we use them in our classroom work, suddenly, subconsciously, things feel richer and more purposeful. I got so swept away after I took this photo that, taking a cue from T. S. Eliot, I decided to eat the peach.

... View more

3

0

4,599

Macmillan Employee

04-26-2016

08:47 AM

Joshua Gunn is an Associate Professor of Communication Studies and Affiliate Faculty in Rhetoric and Writing at the University of Texas at Austin. He is the author of the forthcoming public speaking text, Speech Craft. Photo courtesy of Joshua Gunn Q: What advice do you give your students who have public speaking anxiety or general communication apprehension? JG: In popular culture, we tend to think about public speaking – and communication in general – as a kind of performance that one does well or poorly. I think this image of communication is really intimidating and puts too much pressure on folks. If we think about communicating with others as an attempt to build relationships – an attempt to celebrate the community – speaking can feel much less daunting. Practice, of course, helps a ton too. So my advice is to re-imagine what speaking to others is really about and then to practice it. Q: How do you prepare for a speech? JG: The very first things I need to know when preparing for a speech are (1) where I’m speaking; and (2) who will be in the audience. I ask questions of the person who asked me to speak to get a better sense of the room, the technology that I can use, and the size and demographics of the audience. When I can imagine the audience in my head, I have a much easier time going through a speech and thinking about what examples might be appealing or off-putting, what outfit to wear, what technology I can use, and so on. Now, it’s often the case that I’m asked to speak when the host has no idea what the room I’m speaking in will look like. When that happens, I try to sneak a peek of the room on a day before the speech or a few hours before my speaking engagement. Having a mental image of the speaking space and possible audience helps me visualize success and adapt to my audience. I often make a mini-movie in my head of my future speaking engagement and the audience I’m speaking to. This movie always goes well. I envision succeeding. That really does help me when I actually speak. Q: Have you ever experienced a bout of severe speech anxiety? If so, how did you deal with it? JG: I almost always have speech anxiety when I speak. I’m least anxious speaking mid-semester during teaching because (a) I do it every day; and (b) I know my students by then. But when I teach the first week of class, I get nervous. I think speech anxiety is actually a good thing because it makes you more attentive and sensitive to the speaking situation, your audience’s needs, and so on. I recently had severe anxiety when I was guest speaking at a university. I was really nervous because two good friends, two very respected faculty members, came to the speech. I got so nervous because I wanted to impress them. I remember that I got short of breath. I knew at the moment that it was speech anxiety, and as I talked, my breathing became more labored. I remember I stopped in the middle of my speech, smiled, and said to the audience, “I’m sorry, I believe I’m coming down with something. If you’ll pardon me just a moment.” I took a drink of water and then calmly began my speech again. I finished the speech fine, and as it turned out, I did come down with a cold the next day. But to be honest, I just needed to pause and gather my wits as the wave of anxiety came over me. Just pardoning myself, taking a moment, and getting some water made a big difference. Today I suspect that no one remembers my little “break” during that speech. Q: Have you ever spoken to an audience that was not receptive? How did you handle the situation? JG: Yes, and more often than you might think. I speak a lot as a part of my job, and most audiences are very receptive. The toughest audiences are usually comprised of faculty from academic departments who have assembled to watch me deliver an “academic job talk,” which is a speech professors give to other professors about their research, as part of a job interview. Because audiences at this kind of speech are responsible for hiring what may be a life-long colleague, the stakes are much higher than a regular academic speech. During a recent “job talk” at a big public university, my audience was not receptive – and worse, there wasn’t much I could do. I could tell during my speech that many of the audience members weren’t enjoying it. I tried to compensate by smiling more, telling a couple more jokes than I had planned, and acting goofier (“hamming it up”) when telling the jokes. After the speech was over, I could tell it hadn’t been received well based on the feeling in the room and the faces of the audience. It was during the Q&A for this failed speech that I was able to recover. I was asked a series of hard questions about my speech. I listened actively to the questions and then paraphrased them back to each questioner to make sure I understood each question; then I answered the questions as thoughtfully and with as much good cheer as I could muster. A friend in the audience told me later that the Q&A went very well and that my answers to their questions were better than my speech! I think the moral of my story here is this: The reception of a speech is not limited to the speech itself. A speaker can influence how a speech is perceived, understood, and remembered before and after a speech. Speakers should remember that the speech itself may be the “main course,” but often the side dishes and desserts are what win over hearts and minds. Sometimes you can even give a “bad” speech and still get your message across to an audience effectively, as I did. Q: What do you think is the biggest challenge students face now when they enter college? JG: Students have trouble thinking critically and writing well, but that’s not because they don’t want to do those things. Today, secondary education is geared toward taking exams. Although higher education has its fair share of exams, upper-division courses challenge students to think for themselves and “outside the box.” I find that my students are often surprised when I tell them they can write about anything they want to in some assignments. Q: What motivates you to continue teaching? JG: I’m always motivated when students are learning and engaged, and especially when they seem visibly excited about course material. An earnest note from a student about the value of a lesson or course really goes a long way with me. I’m also encouraged when students laugh at my terrible jokes. If they’re laughing at my terrible jokes, it usually means they’re finding the material that is not “a joke” worthy of their attention. On a personal note... Q: How do you spend your time when you're not teaching? JG: I really enjoy cooking and gardening. I also love to see live music when I can. Q: If you hadn't pursued a career in higher education, what career path do you think you would have chosen? JG: I was headed to law school to be a civil rights attorney and advocate before I discovered the academy, so I imagine I would have pursed that. If I decide to embark on a new career path, I’d be interested in training to be a psychotherapist or counselor of some kind. Q: What was the last book you read? JG: A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle. I’m currently reading His Master’s Voice by Stanisław Lem. Q: What book has influenced you most? JG: The Big Orange Splot by Daniel Manus Pinkwater. Q: Where is one place you want to travel to, but have never been? JG: Too many! Scotland is on the top of my list, though. Q: What is something you want to learn in the next year (Communication-related or otherwise)? JG: How to achieve this mysterious thing called “work-life balance.” Q: What is one thing people would be surprised to learn about you? JG: I’m obsessed with sloths.

... View more

2

0

3,996

Popular Posts

Color Theory in Everyday Life

adam_leipzig

Migrated Account

3

0

A Five-Step Model for Speech Preparation

joseph_ortiz

Migrated Account

2

0

Meet the Author - Joshua Gunn

catherine_burge

Macmillan Employee

2

0